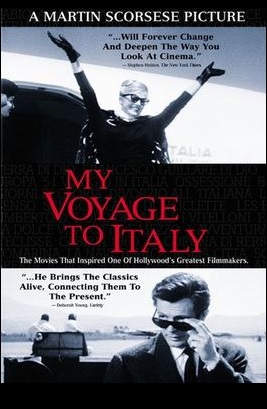

During the recent vacation to Italy with my family, I finally watched Scorsese’s four hour documentary on Italian cinema called Il mio viaggio in Italia, or My Voyage to Italy (1999).

In it, he describes how he fell in love with Italian cinema: “Because so many Italians lived in New York, one channel showed Italian movies on Friday night with subtitles.” Together with his family, he watched as many of them as he could.

When he was a child, Italy was just emerging from World War II, and the aftermath became the central theme of many films from that period. Movies that contained powerful images like nazi soldiers occupying Rome in Rome, Open City (1945, Roberto Rossellini). Despite the often bad quality of the prints, all the essential messages came through, Scorsese recalls.

“Some images were so powerful that they made my grandparents cry”, says Scorsese. “They saw the country they left behind and what became of it. They were feeling protected in the US, but guilty at the same time. These movies could have been about them.”

The first Italian film Scorsese saw was Paisan (1946, Roberto Rossellini). Rossellini’s follow-up to Rome Open City consists of six episodes set during the liberation of Italy. It follows the allied forces as they move through Italy, from Sicily to the northern Po Valley, to drive out the Nazi’s. What impressed him the most were the episodes about people who make the ultimate sacrifices to achieve freedom.

The third part of Rossellini’s post-war trilogy is Germany, Year Zero (1948, Roberto Rossellini). Sacrifice is again a major theme in this movie. “It seems that Rossellini begs the allied forces to look with compassion at their former enemies, so that they could go on together.”

My Voyage to Italy shows long movie fragments, accompanied by Scorsese’s comments. He really takes the time to dissect them, and after each discussion you almost have the feeling as if you have seen them. He covers two main ‘extremes’ of Italian cinema: the epic and the neorealist drama.

The first epic he encountered was Fabiola (1947, Alessandro Blasetti). Its monumental imagery inspired him so much that he drew storyboards for Roman epics of his own. Later, he discovered silent masterpieces such as Cabiria (1914, Giovanni Pastrone), which he describes as “like watching a journal from ancient Rome.”

After World War II, the Italian film industry lay in ruins. With minimal resources to express themselves, filmmakers created the neorealist movement. They depicted the struggles of their nation with stark honesty, relying on non-professional actors and real locations. “Illusion took a backseat to reality”, Scorsese explains.

Neorealism had tremendous influence over cinema that is still felt today in cinematic movements all over the world. It gives audiences raw, human experience – and shows us the heroes and heroines of everyday life.

The most famous example is probably Bicycle Thieves (1948, Vittorio De Sica) about an unemployed man who desperately needs work to support his wife Maria, his son Bruno and his small baby. When everything he tries fails, he steals a bicycle, which leads to dire consequences. It’s an extremely touching film, a specialism of its director Vittorio De Sica.

An earlier film De Sica made is also discussed. It is called Shoeshine (1946) and it triggers much of the same emotions as Bicycle Thieves. Two boys who shine shoes (does the famous GoodFellas line come from here?) end up in prison, which is depicted as hell on earth. Here they are eventually forced to betray each other. Like Bicycle Thieves it has very moving moments involving children. Orson Welles once said that he could never do what De Sica did with Shoeshine, which is making the camera disappear.

In 1952, De Sica made Umberto D., which Scorsese finds an even better film than Bicycle Thieves. This time the story follows an elderly man who, penniless, cares only for his beloved dog. It contains many heartbreaking moments. After seeing Umberto D., the Italian Minister of Culture wrote in an open letter that he hated neorealism, and he asked the filmmakers to be more optimistic.

Perhaps in response, De Sica’s next film, The Gold of Naples (1954), embraced a lighter tone. Though comedic in spirit, it still carried an undercurrent of tragedy. This seamless interplay between drama and comedy, Scorsese notes, is a defining quality of Italian cinema: “Actors can walk the razor-thin line between comedy and drama.”

In the third part of the documentary, Scorsese discussed a different kind of filmmaker: Luchino Visconti. Visconti came from a prominent, wealthy Italian family. But he was also a lifelong member of the communist party. He didn’t have to work, so he felt a little aimless. In the 1930’s he worked for French director Jean Renoir and this influenced him greatly. A hallmark of his films would be exploring the European aristocracy.

But his first film is not about that. Obsession (1943, Luchino Visconti) is seen as a forerunner of the neorealism movement. But, Scorsese says, it is a very stylized movie. “It’s a melodrama with a very earthy sensual feel to it. All Visconti’s gifts were already there: His eye for detail, his mastery of the camera and most of all his operatic sense for action and emotion.”

His follow up was The Earth Trembles (1948, Luchino Visconti) about a group of Sicilian fishermen who rebel against northern middlemen. Besides film, Visconti also started a theatre group that included a young Marcello Mastroianni. This experience is clearly put to good use for Visconti’s next film: Senso (1954). Set during the Italian-Austrian war of 1866, it vividly recreates the 19th century. “He really brought the era to life”, says Scorsese, “not just in how it looked, but in how it felt.”

Finally, Scorsese turns to Federico Fellini, often regarded as the Italian filmmaker. Fellini’s early film I Vitelloni (1953) is an autobiographical tale of five young men in Rimini, torn between staying home and pursuing their dreams. Scorsese deeply identified with them, drawing inspiration for his breakthrough film Mean Streets (1973).

Fellini’s international breakthrough came with La Dolce Vita (1960), a modern reflection on freedom and decadence in the shadow of the Cold War. To escape dread, people plunge into endless pleasures and distractions. This was Fellini’s first collaboration with Marcello Mastroianni, with whom he would make five films – an artistic partnership akin to Scorsese’s with Robert De Niro and later Leonardo DiCaprio.

His follow-up, 8½ (1963), became a personal touchstone for Scorsese. “La Dolce Vita was only the calm before the storm”, he says. “With 8½ he reinvented himself, and in doing so, reinvented cinema.”

The film boldly dramatizes Fellini’s own artistic crisis. Mastroianni plays Guido, a director unable to complete his next project, searching in vain for inspiration. The film becomes a tapestry of dreams, memories, and anxieties, unfolding as a stream of consciousness rather than a conventional plot. For Scorsese, “8½ is the purest expression of love for the cinema that I know.”

The documentary ends with this tribute, leaving us with great words of inspiration from one of the greatest living filmmakers.