Mr. Scorsese is a five episode film portrait about one of the greatest film directors of all time now playing on Apple TV. It’s the most extensive documentary ever shot about the Italian American cinematic master, featuring interviews with a.o. Leonardo DiCaprio, Robert De Niro and Daniel Day Lewis. Reason enough for me to subscribe to Apple TV. An additional benefit of the subscription is that Marty’s latest film – Killers of the Flower Moon – is also available on the channel.

Scorsese is a very sympathetic guy; I have seen many interviews with him before, logical since he’s my favorite filmmaker, but in this series, you really get to know the man. He grew up in Little Italy and later Manhattan. He was very asthmatic as a child and he couldn’t play outside. There is this shot in GoodFellas where a young Henry Hill is staring out of the window observing the wiseguys outside. That’s Marty right there.

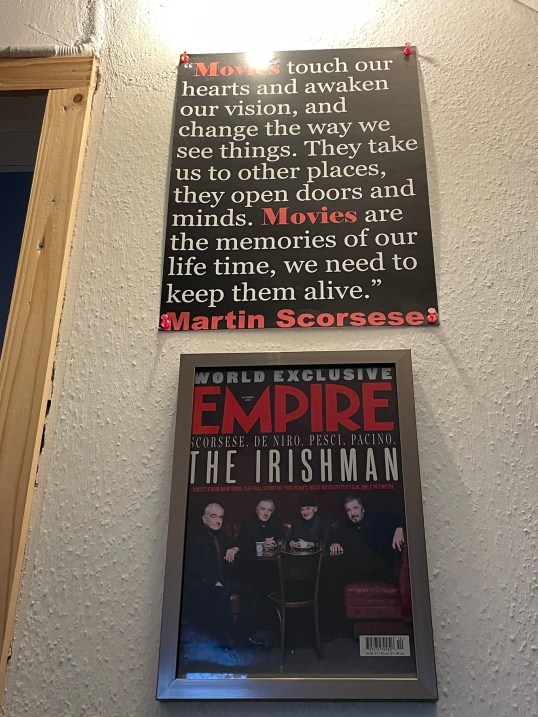

Movie theaters had air conditioning, so that’s where young Martin wanted to be as much as possible. He could breath there, and the movies formed his mind. At home he watched old Italian films with his family. He started making extensive storyboards which his father thought wasn’t very manly. Marty learned of the mobsters who controlled much of the economic activity in his neighbourhood. His father had a good job in the garment industry, which was worked out by the mob. He told young Marty: “Don’t ever let them do you a favor. They’re nothing but bloodsuckers.”

The young Scorsese initially wanted to become a priest, but that path wasn’t for him. Neither were the streets. Literature wasn’t part of his culture either, but a priest encouraged him and his friends to look beyond what they knew; to go to college, to read, learn, and explore. He attended a talk about film school and heard a professor speak passionately about cinema. That was the moment he knew what he wanted to do.

At New York film school he met Thelma Schoonmaker, his future editor. She recalls seeing his student work and knowing immediately that “he had it.” His student film It’s Not Just You, Murray! (1964) won the award for Best Student Film. In 1967 he made his first feature, Who’s That Knocking at My Door, starring Harvey Keitel.

Scorsese married young, but his first marriage collapsed quickly because his mind went more and more to making movies. He went to Hollywood to further his career and met an amazing assortment of talent there: Coppola, Schrader, Spielberg, Lucas and De Palma, known collectively as the ‘Movie Brats’. They were given this name because they were the first generation of formally trained filmmakers to unite film knowledge with artistic ambition.

In the early seventies, King of the B-movies Roger Corman gave Scorsese the chance to direct a movie. This became Boxcar Bertha (1972), a Bonnie and Clyde-style crime movie. His artistic friends hated it. Marty thought it was a good practice in shooting on budget and shooting on time, but his friends thought he had betrayed himself as an artist.

John Cassavetes had seen his feature Who’s That Knocking at My Door and advised him to make more personal movies like that. About Boxcar Bertha he said: “You just spent a year of your life making a piece of shit. Don’t do that again.” Scorsese showed him his Mean Streets screenplay and Cassavetes told him to go find a lead actor to star in it. Then he met De Niro who was from the same neighbourhood.

Mean Streets was based on people and experiences from his neighborhood and people fell in love with it, because it felt completely authentic. That makes sense, because it was real. Now, Marty got more opportunities. With his next film Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (1974), he showed he could also direct women. Ellen Burstyn won the Academy Award for Best Actress for her lead role.

Although Scorsese gained recognition, this period also marked the start of heavy drug use. Film remained his way of working through deep inner turmoil. Drawn to darker characters, he was captivated by Paul Schrader’s script for Taxi Driver. He and De Niro set out to portray a loner like Travis Bickle without turning him into a caricature. Travis is isolated in almost every frame. Taxi Driver (1976) was a huge critical success and won the Palme d’Or.

Everybody praised it. It hit a nerve and showed a true understanding of the American unconscious. A lone man who commits atrocities, like the snipers who killed politicians at that time. Travis has a saviour complex: he wants to save the girls and kill the bad guys. The final scene was too violent for the sensors, so Scorsese changed the colour of the blood to dark, rusty brown or brownish-pink rather than bright red. Daniel Day Lewis was hypnotized by the film and went to see it five or six times. It was the first time he saw Bob (De Niro) act, which was a big thing for him.

After the success of Taxi Driver, he made the costly musical failure New York, New York (1977). His second marriage also fell apart and what started then was a period of self destructive behavior. He started doing lots of drugs and tried to find his cinematic muse again. He almost died – and part of him wanted to because he didn’t know how to create anymore. De Niro had a big part in getting him back on his feet. They went to Sint Maarten where they worked on the script for their next masterpiece: Raging Bull (1980).

Thelma Schoonmaker explains the film’s shooting and editing, and the documentary allows you to rediscover the beauty of its black-and-white imagery. It’s a true work of art. Scorsese had found his muse again, and also his third wife: the daughter of Ingrid Bergman and Roberto Rossellini.

After Raging Bull he wanted to do Gangs of New York and The Last Temptation of Christ. The scripts were there, but the movies were too expensive to make at that time. He did another project with De Niro, The King of Comedy (1982), which flopped. Scorsese’s career was now once again in a bad state. “He was done for in Hollywood”, they told him.

He made a comeback with After Hours (1985), an odd ball comedy shot on a low budget. Key to the film, Scorsese explains, was the collaboration with Director of Photography Michael Ballhaus, who would later shoot GoodFellas. In 1985, he married for the fourth time, this time with Barbara De Fina, who would produce a number of his movies, including Casino.

The re-established Scorsese followed up After Hours with The Color of Money (1986), a pool hall movie starring Paul Newman and Tom Cruise, and a sequel to The Hustler (1961). The movie did well, so now Scorsese could finally make his beloved project The Last Temptation of Christ (1988). He made the film to “get to know Christ better”, he explains.

The budget was tight, so he could only do two takes of every shot during the difficult shoot in Morocco. It was very tough, he says. Even tougher was the reception of the film: people were very upset. It was banned in Rome, Israel, and India – and someone set off a bomb during a screening in Paris. Blockbuster didn’t carry the film. Marty needed FBI protection for the second time (he had gotten threats after Taxi Driver and had needed protection then as well).

While working on The Color of Money, Scorsese read Wiseguy by Nicholas Pileggi, the true story of mobster Henry Hill and his life within the Lucchese crime family. Pileggi and Scorsese had both grown up in the same neighborhood and collaborated on the screenplay for GoodFellas. Scorsese had the film fully mapped out in his head – frame by frame, song by song. The result is pure montage, weightless and electric. Scorsese created a new cinematic language for this movie. “It has this crazy energy”, says Spielberg. “Like a runaway train.”

Previews strangely enough saw a lot of walk-outs. Executives wanted him to cut out the last twenty minutes, which is the whole cocaine sequence. Marty stood up to them and saved the movie. God bless him.

After GoodFellas, Scorsese worked with De Niro again in Cape Fear (1991), a successful remake of the 1962 thriller – and in 1995 they made another mob masterpiece with Casino. It’s about mob guys who were given paradise with Las Vegas – but they got kicked out of paradise because they are so evil. The movie has a unique structure like GoodFellas, but it takes it one step further.

In between, he explored another closed society with The Age of Innocence (1993), his first collaboration with Daniel Day-Lewis. It’s about a man imprisoned by the culture he belongs to, and a great love doomed to remain unconsummated.

In 1997, he returned to another genre he loved to do: the spiritual film. Kundun (1997) is about the Dalai Lama in Tibet. There were no actors in that country, so he had to get all these performances out of non-actors. The film was panned-down as dull. Then came Bringing Out the Dead, a loose follow-up to Taxi Driver, but it was still born at the box office.

Scorsese was dead again, but then who came knocking? Leonardo DiCaprio was now Hollywood’s new golden boy, a guaranteed name for box office success – and a movie star with resources to invest in the projects he chose to star in. Now, Scorsese finally got the opportunity to make his long awaited dream: Gangs of New York (2002).

The film reconstructs 1860s New York in massive sets built in Rome. This was the Five Points neighbourhood, which was dominated by gangs. Scorsese calls it science fiction in reverse. George Lucas came to visit the sets and said that “this is the last time sets like this will ever be built”.

The film has an uncanny reverence to today’s political violence, with the natives who can be seen as the proud boys of that time. People who claim to be the only true Americans and are prepared to use savage violence on immigrants.

Fortunately, the very expensive film – that was produced by Harvey Weinstein – did well at the box office.

He continued to work with DiCaprio, first on The Aviator (2004), a biopic about Howard Hughes, a man obsessed with filmmaking and aviation. The film received 11 Oscar nominations, and then it dawned on the film community that Scorsese never won an Oscar. But, even though The Aviator won in nearly every category, it lost the director award to Clint Eastwood for Million Dollar Baby.

But two years later, they made it up by giving him the Oscar for The Departed (2006), another gangster film. It was awarded to him by his old friends George Lucas, Steven Spielberg and Francis Ford Coppola – a bittersweet moment. In 2010, he made another film with DiCaprio, Shutter Island. And to complete the streak with Leo, he made The Wolf of Wall Street (2013), a commentary on how excessive and moralless capitalism has overtaken our society.

Marty once again portrays the dark side of human nature in all its forms, including terrible domestic violence. Scorsese has often been accused of glorifying bad behavior, but another way to see his work is that he refuses to sanitize human nature. The Wolf of Wall Street was a massive success, tapping directly into post-financial-crisis anger.

The documentary concludes with The Irishman (2019) and early footage from Killers of the Flower Moon (2023). We also see Scorsese at home, caring for his fifth and final wife, Helen Schermerhorn Morris, who suffers from Parkinson’s disease. It’s deeply moving to see the great filmmaker in this intimate setting.

Steven Spielberg provides the perfect closing tribute for this must-see documentary about the legendary director: “There is only one Marty Scorsese. He is a cornerstone of this art form. There is nobody like him and there will never be anybody like him again.”

Indeed.