‘You don’t make up for your sins in church. You do it in the streets…’

Directed by:

Martin Scorsese

Written by:

Martin Scorsese

Mardik Martin

Cast:

Harvey Keitel (Charlie Cappa), Robert De Niro (John ‘Johnny Boy’ Civello), David Proval (Tony DeVienazo), Richard Romanus (Michael Longo), Amy Robinson (Teresa Ronchelli), Cesare Danova (Giovanni Cappa), Victor Argo (Mario), George Memmoli (Joey ‘Clams’ Scala), Lenny Scaletta (Jimmy), Jeannie Bell (Diane)

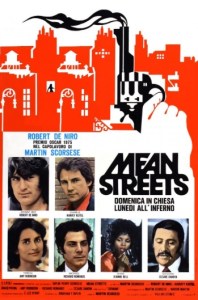

Mean Streets marks the first collaboration between Martin Scorsese and Robert De Niro and right out of the gate, it’s a masterpiece. Set in the tight-knit world of Little Italy, the film follows four small-time hustlers: the conflicted Charlie (Harvey Keitel), hot-tempered bar owner Tony (David Proval), dim-witted loan shark Michael (Richard Romanus), and the reckless wildcard Johnny Boy (Robert De Niro).

Although it isn’t technically Scorsese’s debut, it feels like it. This is the movie in which his voice fully emerges for the first time. It showcases early yet commanding performances by Keitel and De Niro, two actors who would become his most trusted collaborators. Many of the hallmarks of Scorsese’s later masterpieces are already present: the gritty New York setting, the soundtrack full of sixties pop classics, the collision of religion and crime. This isn’t exactly a gangster film – it’s about small-time crooks – but it plays like a prelude to GoodFellas, with dialogues and moral tensions that already sound familiar.

Scorsese immediately sets the tone with a Super 8 projection of Charlie wandering the streets, underscored by the Ronettes’ ‘Be My Baby’. From there, we trail Charlie through his daily routine: drinking in bars, running minor cons, wrestling with Catholic guilt in church visits, and trying to reconcile his moral compass with his ambition.

Charlie wants to rise in the underworld by aligning with his mob-connected uncle, but his loyalty to Johnny Boy – a man drowning in debt and chaos – pulls him down a dangerous path. That loyalty is both touching and toxic, and Scorsese makes it clear early on that violence is never far away. A brutal barroom shooting foreshadows the storm gathering around these characters.

The film’s raw power lies in its atmosphere. Scorsese layers the story with a soundtrack of rock ’n’ roll classics – the Stones’ ‘Jumpin’ Jack Flash’ among them – injecting energy and immediacy into every scene. His restless camera, the naturalistic dialogue laced with profanity, and the lived-in performances combine to create a world that feels authentic and alive.

De Niro is magnetic as Johnny Boy, unpredictable and dangerous yet oddly charming, while Keitel gives a deeply human performance as Charlie, a man torn between sin and salvation. Their chemistry is the film’s beating heart. Scene after scene burns into memory: a drunken spree, a hilariously chaotic bar fight, an explosive confrontation on the street. The pacing is electric, and the details are so rich you’ll want to revisit it just to soak up more of Scorsese’s vision.

The film still feels fresh today. It is utterly original, with no real comparison except some of Scorsese’s later work. Mean Streets doesn’t just hint at the brilliance to come; it announces the arrival of one of cinema’s great storytellers.

Rating:

![]()

Quote:

CHARLIE: “You know something? She is really good-lookin’. I gotta say that again. She is really good-lookin’. But she’s black. You can see that real plain, right? Look, there isn’t much of a difference anyway, is there. Well, is there?”

Trivia:

The opening words are actually spoken by Martin Scorsese, not Harvey Keitel as we are led to believe.