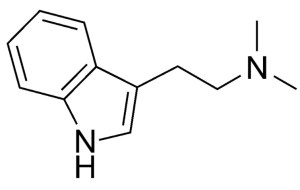

“A fraction of a milligram and everything changes. A molecule that alters your consciousness. An unforgettable experience.”

On April 16, 1943, Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann, working at the Sandoz laboratory in Basel, accidentally ingested a small dose of LSD. Suddenly, he felt as if he were in another world. Fear gripped him: he worried he might never return to his wife and child, and panic set in. But later, the fear gave way to a positive wave. Afterwards, Hofmann felt he had crossed to the other side and returned.

Hofmann had been searching for a medicine to improve circulation. His work led him to ergot, a fungus that grows on rye and related plants. From this he synthesized LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide), a substance chemically related to psilocybin, the psychedelic compound found in magic mushrooms. At first, Hofmann did not know what had caused his extraordinary experience, but he soon realized it must have been the compound he had created.

At Sandoz, researchers recognized LSD’s potential value for psychiatric research. Samples were sent to Stanislav Grof, a Czech-born American psychiatrist and consciousness researcher. This marked the beginning of Grof’s decades-long exploration of non-ordinary states of consciousness.

Grof saw LSD as a catalyst. It does not create these experiences, he argued, but makes them accessible. “In that sense”, he said, “LSD is comparable to what a microscope is for biology or a telescope for astronomy. We don’t think the microscope creates worlds that are not there, but we cannot study these worlds without the tool.”

During the Cold War, the CIA became interested in LSD as a possible truth serum. The problem was that they were seeking predictable outcomes and LSD does not work that way. It was also considered as a potential weapon to incapacitate the enemy.

So how does LSD work? Our consciousness is the sum total of everything our senses perceive. LSD amplifies these senses dramatically. Psychedelic sessions can take people further than years of psychoanalysis.

In a positive experience, users may feel the ego dissolve, boundaries melt away, and control loosen. This can be deeply pleasant. Space and time lose their meaning; experience flows freely until one becomes pure experience itself.

In the 1960s, the psychedelic revolution erupted. The Merry Pranksters, led by Ken Kesey – author of ‘One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest’ – embraced LSD and drove a brightly painted bus across America, inviting people to experience it for themselves.

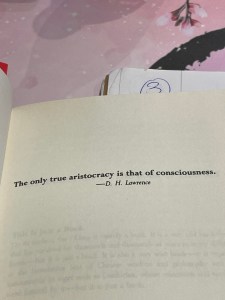

In Millbrook, an abandoned estate in New York, psychiatrist Timothy Leary and Ralph Metzner established a psychedelic research center where anyone could participate. LSD was seen as a great equalizer. No matter one’s social background, the experience could dissolve hierarchy and expand cosmic understanding.

“We teach people to turn on, go out of their minds, and tune in”, Leary said. “The country is an insane asylum, focused on material possession, war, and racism.” His ambition was nothing less than a spiritual revolution, achieved by millions of people using LSD regularly.

Hofmann strongly objected to this approach. LSD, he warned, was a powerful instrument that required a mature mind. Promoting it indiscriminately to young people was irresponsible.

LSD often triggered strong anti-war sentiments, rooted in transpersonal experiences of unity with nature and all living beings. This directly challenged conservative values. In the United States, amid the escalating Vietnam War, tensions between the counterculture and the establishment grew. LSD became a convenient scapegoat for social unrest, and the government launched an aggressive – and often absurd – propaganda campaign.

In 1966, LSD was outlawed in California. In 1967, President Nixon declared Timothy Leary “the most dangerous man in America.” Grof later remarked, “In the irresponsible hands of Leary, it came to be seen as dangerous and that killed nearly all possibilities for research.”

Some clinical work continued for a while. Grof conducted LSD sessions with terminal cancer patients, profoundly altering their relationship with death. Many became reconciled with the fact that they were dying. “In our culture”, Grof said, “we are programmed to think we are only our bodies. LSD can show you that you are part of something much larger.”

Soon, however, LSD was internationally demonized. Research disappeared underground and remained there for decades.

Albert Hofmann died on April 29, 2008, at the age of 102. He never denied LSD’s risks, but he also believed its greatest danger lay in misunderstanding it. For Hofmann, LSD was not an escape from reality but a doorway… A doorway that, if approached with care, could reveal how vast and mysterious consciousness truly is.

The documentary ‘The Substance: Albert Hofmann’s LSD’ is available for rent on the Apple TV app.