DMT (Dimethyltryptamine) is an extremely powerful hallucinogenic found throughout nature that has a profound impact on human consciousness.

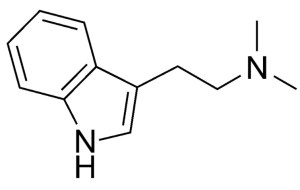

The structure of DMT is very simple: there are only four positions where chemical groups can attach. It’s everywhere in nature. All organisms have the two key enzymes that lead to the synthesis of DMT. It is also the visionary ingredient in ayahuasca, a very popular psychedelic in the West nowadays.

Ayahuasca is created by combining two Amazon plants, one containing DMT and one containing an enzyme inhibitor, needed for the DMT to have effect. How did these Amazonian Indians know how to combine these plants? A trip created by orally consuming DMT can last three to four hours. That is much more time than the bullet train trip you get when smoking or injecting DMT.

So DMT is everywhere in nature, but what is it for? Many leading experts say they are messenger molecules. It is a powerful tool to explore the whole mysterious question: what is consciousness?

DMT is often referred to as the spirit molecule, which is a conundrum. The spirit is the inner world and the molecule is the external world. So the psychedelic is an entheogen; they take us from the science to the spirit.

DMT can also be produced by the human brain in extremely small amounts. The enzymes necessary for its production are expressed in the cerebral cortex, the choroid plexus, and the pineal gland.

Rick Strassman – a professor in psychiatry – has done extensive research in DMT and non-ordinary states of consciousness. It is his belief that the pineal gland, a tiny, pinecone-shaped endocrine gland in the center of the brain, at times releases DMT to facilitate the entering and exciting of the soul in the body.

Through various practices, like fasting, chanting and praying, a release might be triggered that is correlated with mystical experiences. A DMT trip is described as a ‘psychedelic bungee jump’. Just like that, you find yourself in a completely different reality, and – bang! – just like that, you’re out of it again.

Why are these plants made illegal in our ‘enlightened’ Western societies? “It is very revealing about these societies”, says writer and journalist Graham Hancock. “Our society devalues non-ordinary states of consciousness. Any other consciousness that is not related to the production or consumption of material goods is stigmatized in our society today.”

There is fear in the powers that be that ended the psychedelic revolution in the sixties. Fear that if enough people take these substances, the very fabric of our societies would be picked apart.

After a near ban of psychedelic research, Rick Strassman got approval in 1989 to do a DMT study. It was the first psychedelic research in a generation. He did not approach the work as psychotherapy, but as pure scientific research, focusing on what happened in the body and brain. He recorded the experiences of participants and later published them in his book ‘DMT: The Spirit Molecule’, a fascinating byproduct of the study.

So what is the experience like? Time crumbles. The linearity of time is totally meaningless in a DMT experience. You are at the God Head, the point where all time folds in on itself. You are no longer a human being. In fact, you are no longer anything you can identify with. It is a terrifying experience. You are blasted out of your body at warp speed, backwards through your own DNA out the other end into the universe.

DMT users often report encountering pure consciousness, sometimes perceived as a vastly advanced civilization; far beyond anything known on Earth. “My sense was that at some point there was an implicit realization: this is the divine realm”, one user said.

“It’s a place I’ve been many times before. A place where souls await rebirth. An incredible, transcendent peace came over me. I have never felt such peace in my life. Every fear, hope, and attachment to the material world was stripped away. I was free to simply be the essence of a soul.”

Strassman’s explanation: The brain, the organ of consciousness, was transformed in such a way that it could receive information that it couldn’t normally receive. “It rips that filtering mechanism away for just a few minutes and for this time you are immersed in raw data: sensory input, memories, associations. It seems your brain builds reality out of these things. You associate and synthesize these things together and tell yourself a story basically.”

During DMT experiences, encounters with aliens, angels, and other entities are common, as are visions of other civilizations. An intelligence is often perceived, one that does not seem to exist within three-dimensional space.

DMT is a messenger that offers a glimpse into possible future stages of human evolution. It may be the ultimate psychedelic compound: a doorway to another reality.

The documentary ‘DMT: The Spirit Molecule’ is available on YouTube.