‘Ticket to Ride’ glints with meanings; you can walk around it forever and see different shafts of light bounding off its surfaces. It’s about a break-up, viewed through a haze of pot smoke. It’s about a generational shift in the balance of power between men and women. It’s about a shift in the balance of power between John and Paul, as John comes to suspect that Paul doesn’t rely on him quite as much as he relies on Paul.’

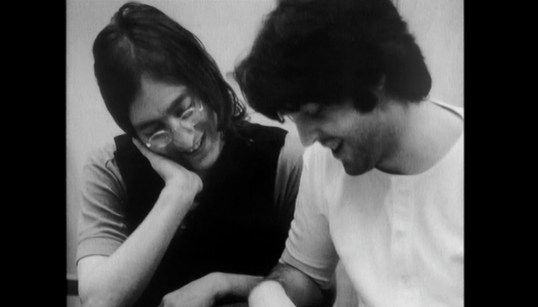

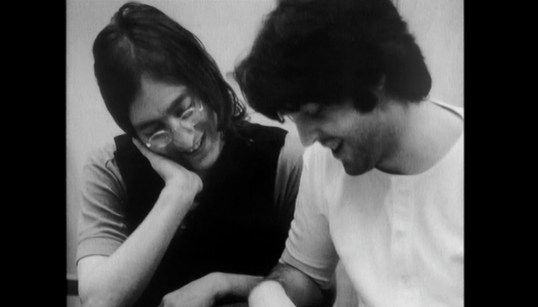

This new book by British author Ian Leslie tells the story of John Lennon’s and Paul McCartney’s intimate relationship. Starting with their first meeting at the Woolton Village Fête and ending with Paul’s response to John’s death in 1980. It tells the story by way of the richest primary source of all: the songs they wrote together. Each chapter is anchored in a song that tells us something about the state of their relationship at that time. The main point is that even after the Beatles broke up, John and Paul were inseparable. They merged their souls and multiplied their talents to create the greatest bodies of music in history.

This is also a love story. John and Paul were more than just friends or collaborators in the sense that we normally understand these terms. Their friendship was in a sense a romance, full of longing and passion, riven by jealousy.

The biographical stories told aren’t new – although I certainly learnt new things – but Leslie’s approach still feels fresh. The psychology behind the stories is what sets it apart. Every anecdotal story is approached by how things must have felt and been experienced by John and Paul. It delves into their state of mind at the time certain songs were written.

The first song Leslie discusses is ‘Come Go With Me’, which John performed with the Quarrymen at the Woolton Village Fête. His improvised lyrics impressed Paul, who realized they might connect through a shared passion for music and songwriting. It moves on with their first songs: ‘I Lost My Little Girl’ by Paul and ‘Hello Little Girl’ by John. This was right away the first instance in which the two were borrowing and building on each other’s ideas.

They began writing songs together, something nobody was doing at that time except the Great Ones from America. The two trusted each other enough to let the other hear their unfinished work, and the more they shared the closer they became.

They bonded even more deeply over the loss of their mothers—Paul at 14, John at 17. Paul: “Each of us knew that had happened to the other. At that age you’re not allowed to be devastated and particularly as young boys, teenage boys, you just shrug it off.” It shattered them he later said, but they had to hide how broken they felt. “I’m sure I formed shells and barriers in that period that I’ve got to this day. John certainly did.”

Shells and barriers are defensive fortifications, but for John and Paul this shared trauma also blasted open an underground tunnel through which they were able to communicate in secret from the rest of the world, and even from themselves. In music they could say what they felt without having to say it at all. In 2016, McCartney told Rolling Stone Magazine: “Music is like a psychiatrist. You can tell a guitar things that you can’t tell people. And it will answer you with things people can’t tell you.”

The story goes on with their rise in Hamburg and then in Liverpool. Those who knew the pair marveled at how close they were. Bernie Boyle, a Cavern regular who did some work for the Beatles as a roadie, observed their eerie mental connection: “They were so tight, it was like there was a telepathy between them: on stage, they’d look at each other and know instinctively what the other was thinking.”

People were drawn to them, but were also wary of them, for both were capable of shriveling outsiders with wit. Together they had an aura of unbreachable assurance. This was partly the arrogance of the damaged. The well known trauma psychiatrist Bessel van der Kolk observes: “After trauma the world becomes sharply divided between those who know and those who don’t.”

In their early years, McCartney brought in ballads to their performances like ‘Till There Was You’. John felt discomfort during those moments, but he realized that these songs contributed to the band’s more varied approach than just rock ‘n roll. Besides, John – despite his tough image – secretly also loved the genres that they both got familiar with in their childhood, like folk, music hall, jazz and show-tunes.

It was the song ‘Please Please Me’ that really got the Lennon-McCartney songwriting partnership going. At that point, it became a second revenue stream within the band just for the two of them. ‘Please Please Me’ was their first number one hit and was the final move towards the Lennon-McCartney songwriting explosion that would soon be unleashed.

The book goes on to describe many of the songs that followed, focusing on how John and Paul conceived them, delivered them, and why their combination of voices and sensibilities made the music so enduring. Leslie also teases out the hidden meanings some songs carried for each of them; messages they sometimes couldn’t say directly.

There were also differences in their approach to songwriting. John’s song ideas were often used as a creative platform to which the others could bring their brilliant contributions. Paul – the most accomplished musician and instrumental allrounder – tended to bring more fully fledged songs to the band with clear ideas of what he wanted.

In the first five albums, John was mostly the song originator of the band. Paul’s ‘Yesterday’ was an important moment in their relationship, argues Leslie. John always felt uncertain about it, perhaps because it showed that Paul was such a brilliant songwriter in his own right and that he could do without John. After the break-up, John wrote ‘Imagine’ and according to a collaborator at that time, John felt he had finally written a melody as good as ‘Yesterday’.

After the creative highlight that was ‘Sgt. Pepper’s’, the disintegration of the band started in John’s mind. During their time in India, John was depressed as evident by songs such as ‘I’m So Tired’ and ‘Yer Blues’. The Beatles had been his closest connection and had pulled him through the most difficult of times. Now, it was time to start anew.

Leslie covers the break-up and post-break-up years in great detail, showing how the songs of that period reflect what was going on in their minds. For example, John’s ‘Look At Me’ – which was written in India – is about John’s sense of identity hanging on by being seen by Paul, his creative partner. And if he is not being seen by Paul, who is he supposed to be?

After the break-up, their connection always remained strong and they always kept communicating through music. There were the famous songs at which they were having digs at each other (‘Too Many People’ and ‘How Do You Sleep?’). There was also the instance of John’s final live performance at a concert by Elton John. He chose three songs to perform and one of them was ‘I Saw Her Standing There’. Why did he choose this Paul-song? Because he was scared and needed to summon Paul to get him though, Leslie argues.

The book ends with John’s murder and Paul’s heartbreaking response. The bond was severed forever, yet Paul found a way to keep speaking to John – as always through music. His song ‘Here Today’ is a conversation with the friend, rival, and partner he could never replace.