Door Jeppe Kleijngeld

‘Uppers are no longer stylish. Methedrine is almost as rare, on the 1971 market, as pure acid or DMT. ‘Consciousness Expansion’ went out with LBJ (Lyndon B. Johnson, red.). . . and it is worth noting, historically, that downers came in with Nixon.’

– Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas: A Savage Journey to the Heart of the American Dream (1971)

Deze must-read klassieker wordt wel samen met ‘Fear and Loathing: On the Campaign Trail ‘72‘ beschouwd als Gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson’s meesterwerk (het is mijn favoriete boek aller tijden). Beide boeken schreef hij in zijn hoogtijdagen begin jaren 70′, een bijzondere, vreemde en bewogen periode waarin Thompson’s creativiteit en talent tot geniale wasdom kwam.

‘We were somewhere around Barstow on the edge of the desert when the drugs began to take hold.’ Dit zijn de beruchte eerste woorden van deze literaire sensatie die veel weg heeft van een op hol geslagen hersenspinsel van Thompson. Zo omschrijft hij het een jaar later dan ook (min of meer) zelf op in ‘Fear and Loathing: On the Campaign Trail 72’. ‘I have a bad tendency to rush off on mad tangents and pursue them for fifty of sixty pages that get so out of control that I end up burning them, for my own good. One of the few exceptions to this rule occurred very recently, when I slipped up and let about two hundred pages go into print… ‘ Hiermee doelt Thompson op de oorspronkelijke tweedelige publicatie van ‘Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas’ in Rolling Stone Magazine op 11 en 25 november 1971.

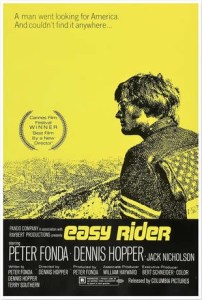

Ter inspiratie van het Fear and Loathing manuscript gebruikte Thompson twee tripjes naar Las Vegas met goede vriend Oscar Zeta Acosta. Deze latino-activist vormde de basis voor het centrale personage Dr. Gonzo. Het werd een krankzinnig, met drugs en ether doordrenkt verhaal, dat als metafoor diende voor Amerika’s ‘Season in Hell’. De vredige jaren 60′ waren voor veel Amerikanen, waaronder Thompson, geëindigd in een complete depressie. Nixon was gekozen tot president en de volledig uit de klauwen gelopen Vietnam oorlog eiste steeds meer slachtoffers.

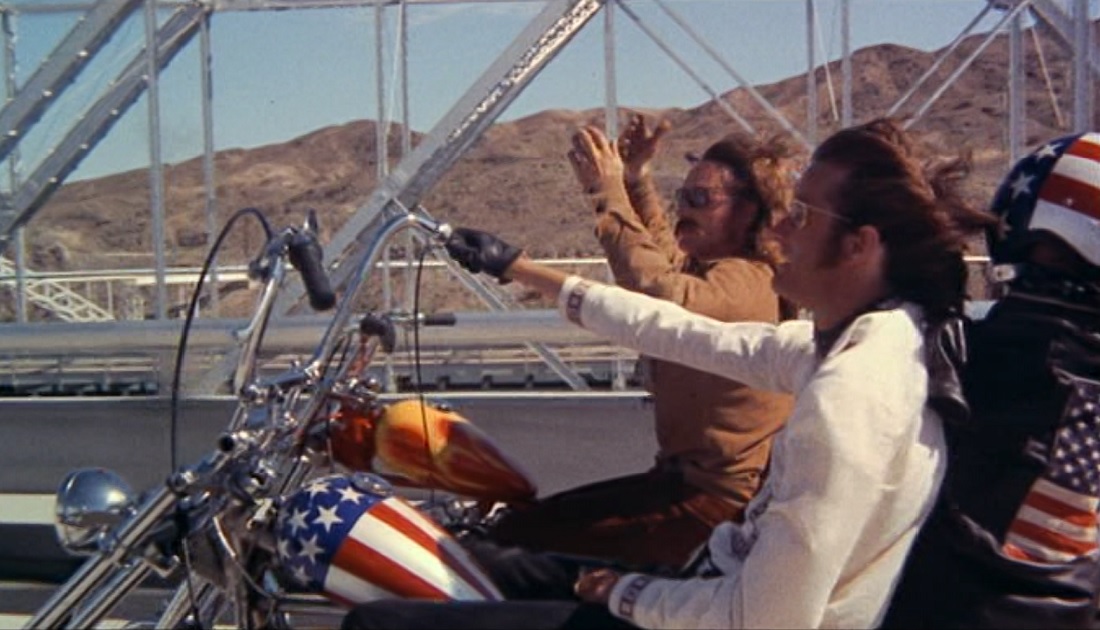

‘Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas’ vertelt het verhaal van de heilige missie van twee vrienden, de freak journalist Raoul Duke en zijn psychopathische advocaat Dr. Gonzo, om de Amerikaanse droom te vinden. Als die überhaupt nog bestond. Ze trekken naar Las Vegas (het zenuwcentrum van de Amerikaanse droom) om een woestijnrace te verslaan, maar al snel verlaten ze het werk en maken ze een serie bizarre en beangstigende trips mee. Daarbij trashen ze hotelkamers, komen ze in extreem angstaanjagende en paranoïde situaties terecht, hebben ze bizarre aanvaringen met representanten van de lokale gemeenschap en moeten ze elkaar behoeden voor totale zelfvernietiging.

De Britse cartoonist Ralph Steadman maakte de geniale tekeningen bij het boek.

Het is een van de grappigste boeken ooit geschreven. Thompson’s gestoorde en paranoïde gedachtegangen zijn zo hilarisch dat ik het boek vaak moest wegleggen omdat ik te hard moest lachen. Vooral (voormalig) drugsgebruikers zullen zich goed kunnen verplaatsen in Thompson’s waanzinnige observaties en belevenissen. ‘By the time I got to the terminal I was pouring sweat. But nothing abnormal. I tend to sweat heavily in warm climates. My clothes are soaking wet from dawn to dusk. This worried me at first, but when I went to a doctor and described my normal daily intake of booze, drugs and poison he told me to come back when the sweating stopped.’

Bij het herlezen van het boek, vroeg ik me wederom af hoeveel van het verhaal echt is en hoeveel verzonnen. Het antwoord staat (min of meer) in ‘The Great Shark Hunt’, een verzameling eerder gepubliceerd werk van Thompson uitgegeven in 1979. Zoals bij vele klassieke verhalen is de ontstaansgeschiedenis van Fear and Loathing een interessant verhaal op zichzelf. Thompson werkte in deze turbulente dagen van de Amerikaanse geschiedenis aan een artikelenreeks over Ruben Salazar, een Mexicaans-Amerikaanse journalist die naar verluidt was vermoord door een Los Angeles hulpsheriff tijdens een anti-Vietnam demonstratie.

Een van de belangrijkste bronnen van het verhaal was Acosta, maar Thompson kon nauwelijks met hem praten omdat diens militante volgelingen geen blanken dulden in hun omgeving, of die van hun leider. Thompson en Acosta besloten naar Las Vegas te gaan waar Thompson de opdracht had om een verhaal te schrijven over de Mint 400 woestijnrace. Hier konden ze ontspannen praten over de kwestie Salazar. Wat volgde staat allemaal in het boek… Met de nodige toegevoegde waanzin uiteraard.

In het artikel over Fear and Loathing in ‘The Great Shark Hunt’ beschrijft Thompson dit boek als een mislukt experiment in Gonzo Journalistiek. Zijn idee was een notitieblok te kopen en daarin alles op te nemen zoals het gebeurde. Vervolgende wilde hij het notitieblok insturen voor publicatie, zonder enige aanpassing of opmaking. Het oog en de geest van de journalist zouden zo functioneren als de camera. Maar dit is verdomd moeilijk, stelt Thompson. Dus werd het een ander soort verhaal als hij oorspronkelijk in gedachten had.

Het magazine Sport Illustrated, waarvoor hij het Mint 400 verhaal zou schrijven, wezen het manuscript af en weigerden Thompson zijn onkosten te vergoeden. Na het vertrek van Acosta uit Vegas zat Thompson daar met een hotelschuld die hij niet kon betalen. Hij vluchtte uit Nevada en dook onder in Arcadia, nabij Los Angeles. In een week van slapen en schrijven tekende hij het Salazar verhaal op. Maar elke avond rond middernacht werkte hij ter ontspanning een paar uurtjes aan het ‘gestoorde’ Las Vegas verhaal.

Toen hij weer in San Francisco kwam bij het hoofdkwartier van Rolling Stone Magazine om het Salazar verhaal door te lopen, nam uitgever Jann Wenner het Vegas manuscript, dat inmiddels 5.000 woorden omvatte, serieus als losstaande publicatie. Thompson kreeg een publicatiedatum en geld om er verder aan te werken. Het eindresultaat kan ik onmogelijk beter omschrijven dan Thompson zelf; ‘Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas will have to be chalked off as a frenzied experiment, a fine idea that went crazy about halfway through… a victim of its own conceptual schizophrenia, caught & finally crippled in that vain, academic limbo between ‘journalism’ & ‘fiction’. And then hoist on its own petard of multiple felonies and enough flat-out crime to put anybody who’d admit to this kind of stinking behavior in the Nevada State Prison until 1984.’

In de oorspronkelijke publicatie in Rolling Stone Magazine stond ‘geschreven door Raoul Duke’. Thompson was bang in de problemen te raken als hij onder zijn eigen naam zou publiceren, omdat hij zichzelf in het verhaal toch afschildert als dronken, hallucinerende crimineel. Toen het boek uitkwam in 1971 waren de kritieken wisselend, maar er waren veel critici die het werk herkende als belangrijke Amerikaanse literatuur. Daarnaast werd het boek een groot cult succes. ‘Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas’ grijpt perfect de zeitgeist van de periode na de jaren 60’ en veel fans voelden zich hierdoor aangetrokken.

In 1996 kwam er een audioboek versie uit van Margaritaville Records and Island Records om het 25 jarige bestaan van het boek te vieren. De stemmen werden verzorgd door Harry Dean Stanton (verteller/Hunter S. Thompson), Jim Jarmusch (Raoul Duke) en Maury Chaykin (Dr. Gonzo). Misschien komt omdat ik de film vaak gezien hebt met de briljante optredens van Johnny Depp en Benicio Del Toro, maar ik vond het een erg slechte audio adaptatie. De stemmen kloppen niet bij de karakters die verbeeld worden en de acteurs lijken zich niet echt in te leven in de teksten.

Het boek was ook voorbestemd om ooit verfilmd te worden. Dit duurde echter een lange tijd. Beroemd animator Ralph Bakshi wilde er een tekenfilm van maken in de stijl van cartoonist Ralph Steadman die de briljante illustraties bij het boek verzorgde, maar dit ging niet door. Tijdens het langdurige ontwikkeltraject van de film zijn verschillende acteurs overwogen. In eerste instantie waren dat Jack Nicholson en Marlon Brando als Raoul Duke en Dr. Gonzo, maar zij werden te oud. Daarna werden Blues Brothers Dan Aykroyd en John Belushi overwogen, maar dat idee ging overboord toen Belushi overleed. Later werd John Malkovich overwogen voor de rol van Duke, maar ook hij werd te oud. Daarna werd John Cusack overwogen die een toneelversie van Fear and Loathing had geregisseerd. Maar toen ontmoette Thompson Johnny Depp en hij raakte ervan overtuigd dat Depp de aangewezen persoon was om Duke te spelen.

De film, geregisseerd door Terry Gilliam, en met Johnny Depp en Benicio Del Toro (als Dr. Gonzo) kwam uit in 1998 en werd – net als het boek – een groot cult succes.

![]()